The Journal

A glimpse into Lee's personal projects, passions, and perspectives.

Discover and shop pieces inspired by the latest influences in interior design.

A curated edit of highlights and intriguing finds from social media.

A glimpse into Lee's personal projects, passions, and perspectives.

Discover and shop pieces inspired by the latest influences in interior design.

A curated edit of highlights and intriguing finds from social media.

Elsa Peretti's breathtaking Casa Grande in San Martín Vell, Spain, is a source of constant inspiration.

Read more

Edith Wharton's 1890 The Decoration of Houses gives surprisingly fresh design advice.

Read more

Flipping through the pages of AD Italia, something of a lightbulb went off. As I stumbled across the otherworldly gallery cum workshop that Florentine antiquarian Monica Lupi calls home, it occurre...

Read more

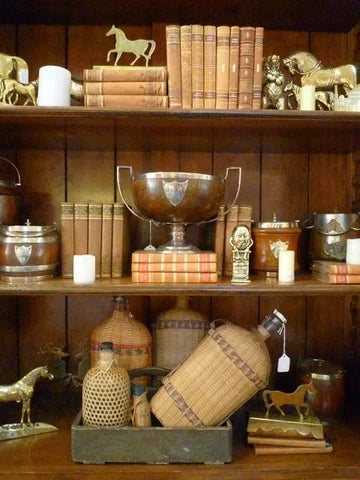

Image of Axel Vervoodt There is no argument that antique furnishings bring a level of experience, knowledge and sophistication into our homes. They take us to a different time and place. They b...

Read more

Lifestyle changes usually happen over years and even decades. If you are like me, you can remember your lifestyle changes at home. Remember when living at home meant living w...

Read more

There is no argument that antiques add a level of experience, knowledge and sophistication to our homes. They bring a layer of history, culture and character into our spaces...

Read more

François Halard via Apartamento Magazine Comfort has come a long way from wooden and stone benches in the Middle Ages, when it was thought that the body was di...

Read more

The Kennels at Goodwood, Sussex I would venture to say that when you are asked what comes to mind when you think French, your answer would be French wine, food, fashion an...

Read more

Open during renovations. Lee Stanton Antiques is proud to announce the renovation of the La Cienega showroom. Thanks to a newly designed showroom front and expanded w...

Read more

The Rise and Fall of Industrial Furniture

Finding their way into our homes, industrial furnitures have become statement pieces because of their strength in form and function. However, have you ever thought of where they came from and w...

Read more

Do You Judge a Book by the Cover?

The Look vs Substance We have all experienced it. We see something from a distance that has the right look, but when we get up close, we realize something is not right; it's a knock of...

Read more

As clients visit my showroom and admire the antiques, they often ask me about their history and, after an explanation, they inevitably respond, "wow, every piece must tell a story." It's tru...

Read more